- Home

- Ivelisse Rodriguez

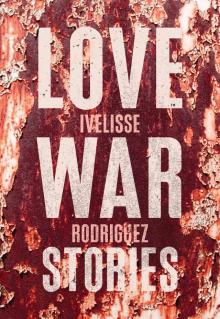

Love War Stories Page 5

Love War Stories Read online

Page 5

Jose waves and gives me a kiss on the cheek. He extends his arm to me and I feel giddy. He has shared his knowledge about the Cultural House with me ever since I began working here and has been my steadfast supporter. He adores Julia as much as I do, but in a different way. He has grown to admire her over the years as a historian putting together the pieces of her life, which has often proven to be a formidable task. I worship her like a child mesmerized by the strength of her father.

We take in the room together, and as we stop in front of a picture of Julia in Cuba, Jose leans in and says, “You look lovely. Like a young Julia de Burgos. Maybe you’ll meet your Grullón tonight, but with a happier ending, of course.” In the photo, she is standing between two men, laughing merrily. She is wearing a white knee-length dress, and while there is another pretty woman in the picture, she is hardly noticeable. Julia has a quiet beauty, the kind that enters a room unobtrusively, not turning heads with a big fuss or a red dress, but standing in a corner and waiting patiently for your eyes to fall upon it, knowing they ultimately will.

My mother doesn’t like the premise for my exhibition. The display revolves around the notion of Julia’s love affairs. I spent countless hours poring over books, talking to professors, and hunting down pictures from El Centro in order to put it together. Pictures of Julia and various rumored paramours are hung around the room, and underneath is a summary of the evidence that a particular poem had been written for that man.

When I first told her about it, her exact words were “Isn’t it sad that a woman can do a great many things, is still noted today as the greatest poet in Puerto Rico, yet all we are concerned about is who she was sleeping with.”

But she should have known that the exhibition was a way to honor my father.

While sitting at a table with some other coworkers, Rosanna whispers in my ear, “Maceo is here.”

I flutter inwardly. He looks the same as he did last summer when he interned with me. Rosanna and I would take turns giggling whenever we saw him in the office. At lunch we would have daily updates of Maceo sightings.

Maceo catches me looking at him, and I blush as he begins to make his way over.

The night that Julia met Grullón, she was at a party in the Dominican Republic. Her first time in the country, she is escorted by Dr. Juan Bosch, an intellectual and the future president, and she is his prize. It remains dubious where his love runs. But Grullón stages a coup d’état that night and every night thereafter as he is the one the majority says she loves enduringly; their names, if not their bodies, entwined forever.

When Maceo reaches us, he gives Rosanna and me a kiss on the cheek.

“This all looks amazing, Maricarmen,” he says, his eyes falling on the different pictures.

“Thank you. I’ve loved living in Julia’s world.”

“Your father would be proud.”

I beam. He remembered.

“So what’s next?” Maceo says as he smiles to his eyes. He is the kind of person everyone has a good word about. He is the kind of man I would watch from afar.

“I just go back to the mundane everyday stuff after this.”

My mother arrives with her colleagues, and as always she is in the front charging the air wherever she steps. She is the woman in the red dress. Before even finding her table, she comes over.

“Let’s dance, you look too pretty to be sitting down,” she says to me.

She twirls me around the floor to the sounds of salsa from her time. I am clumsy and cannot keep up with her. The band then begins to play a rendition of “En Mi Viejo San Juan,” and I hear the excited murmuring of the dancers in recognition of this classic. I am determined to keep up with her. The song must conjure up in them, as it does in me, memories of their youth, their parents or grandparents, whether on the Island or here. My father always played this song, always remembering his parents’ home.

He came to New York in his twenties, right after he graduated from college, and after three months of being in law school, he met a Cuban, Alfredo Montañez, who became my father’s lifelong friend. Alfredo told him how there were throngs of Puerto Ricans living uptown and that he would take my father there sometime. They could go out dancing, meet women, and it would be just like being in Puerto Rico. Alfredo escorted my father around El Barrio, and he was hooked. Arriving in New York on the heels of a new radicalism, my father fell in love with all the political organizing that was going on at the time. He quickly became involved and told his father that he wanted to be a tenant lawyer. There were a lot of people who lived in the filth of the projects, and he spent the rest of his life championing the rights of the people Alfredo had shown him.

My father was the one who introduced me to the works of Julia de Burgos. When he and my mother first met, they spent countless hours reading each other Latin American poetry. “Those were the sixties,” he would joke whenever he told that story. It was his turn to tell me a bedtime story every other night, and he was the best at it. He would pull all these figures from history and make them come alive. He told tales of a young Pablo Neruda and how his words would set a people free, of the Young Lords and how they had hung a Puerto Rican flag from the Statue of Liberty. A few times a month my father told me about Julia because they were both from Carolina, Puerto Rico. He wanted to imbue in me the notion that there were extraordinary people from where he came from. He told me of how Nobel Prize–winning poets singled her out. In all the world, this woman from this tiny island was writing poems that floated from island to island, country to country; a voice that easily could have been obscured, reaching all those disparate parts of the world.

As Rosanna gets up to dance with one of our young interns, she winks at me, as if she is going to feast on him. I laugh and hum along to the music. He doesn’t dance very well, so I watch her lead him around the dance floor.

“Men shouldn’t be allowed to not know how to dance,” she says when she comes back. “What a disappointment.” She critiques everyone’s dance skills until she sees Maceo approaching and brings up how we almost kissed last summer. I was still with Alex, so I had stopped myself. I smack her leg so she will be quiet before he gets to us. Maceo comes up behind me, leans over, and whispers in my ear if I would like to dance.

In an interview about Julia, Dr. Juan Bosch recalls an incident at a party in Cuba where Julia—he remembers her as beautiful—is going from partner to partner until her lover, the infamous heartbreaker Dr. Jimenes Grullón, shows up. He pulls her gently aside, and their loud words overshadow the festive mood. And all the good Dr. Bosch can remember after that is Julia fleeing into the night. He knew the affair had somehow been broken. He goes up to Grullón and shouts, “What happened?” Without waiting for an answer, he leaves in search of Julia, but alas does not find her. I imagine Dr. Bosch slams his fist down on the table at this point in the interview because his affection for her was resilient. Throughout the years, he hears bits and pieces of her life, snatches of conversations that have floated over miles of land and over the Caribbean Sea, which has washed out the truth of any of it. And then he hears of her death in the streets, and Dr. Bosch weeps in ways men are never supposed to.

I smile weakly at Maceo and tell him I am too tired to dance, that my mother wore me out. The difference between Julia and me is that she just looks like the quiet beauty but inside she is the woman in the red dress, and I am not.

One of my favorite pictures in the exhibit is the one where Julia’s body is being returned to Puerto Rico. This photo has nothing to do with Julia’s romantic life per se but is about how much the public cherished her. In his book, Jack Agüeros tells a story of standing with a friend in front of a stoop in East Harlem and a group of men come around a corner with one woman among them. They were all drunk, people that would easily be dismissed. The friend points out that the woman is Julia de Burgos. Agüeros, not knowing who she is, had just taken her for a drunkard. His friend tells him that she is the greatest living Puerto Rican poet.

She

died on the streets of East Harlem and was buried in Potter’s Field. Potter’s Field, where the nameless, the faceless, the poor, go. When the ambulance picked her up, all the paramedics saw was a body that must not have had any identification, a woman who died on the streets of East Harlem alone, with no family, with no one by her side, a woman with the smell of alcohol on her, and they must have thought that no one in all the world could care about a woman like this. And for a while, her body remained underground with the rest of New York’s forgotten.

There is a macabre rumor that Agüeros relates: that part of Julia’s legs were cut off so she could fit in the small pine box the City of New York provided for her burial. But Puerto Rico loved her—it would have outfitted her with more than just a plain pine box. They would have accommodated her legs, all of her limbs.

The coffin, when it finally reached the San Juan airport, was draped with a Puerto Rican flag. In the photo, people from all over Puerto Rico stand at the airport, like they would await returning family members; even though they may have never seen her in life, they have all known her. Have held her picture, read her poems, fallen in love with something . . . enough to give up their work days, give up cooking for their families, give up taking care of their kids, all for a glimpse of a casket draped in a Puerto Rican flag. But it is more than a coffin; they know who lies in it: “La vida, la fuerza, la mujer.”

I recognize their love—the way I think we should all be loved.

“Well, from what I hear Maceo is quite the little star at PRLDEF. His father was a lawyer, and Maceo also plans on going to law school,” Rosanna says.

“Oh, in that case, my mother will think he’s perfect for me,” I reply.

“Hey, well your mother’s not going to be the one sleeping with him.”

“Whoa, we’re not quite there yet.”

“Maricarmen! You’re not a virgin? Are you?”

“No, I’m just extremely choosy as to who I have sex with.”

“Well, how many people have you had sex with?”

“Just two.”

“Two? You might as well be a virgin.”

We start to laugh.

“Shut up. If and when I find the right guy, I will be glad to make it three.”

“Well, I hope you’re not waiting for Prince Charming, Cinderella,” Rosanna says before getting up to dance with the intern again.

Since I broke up with Alex, I haven’t dated anyone. Since I was young, I have always been reclusive. And with the breakup, it’s like I regressed further back into myself, into the world my father created for me. And too often, I have found comfort in that.

My mother and I stand shoulder to shoulder as we have for many years. We are in front of the snapshot taken outside my father’s schoolhouse, and he stands two children down from Julia. I have relished this photo for years.

My mother gazes at my father in the picture. “I wish I had known him then.”

He has been dead for two years. To her, it must seem easy for me. I go to work every day, and it is like he is there with me, sharing another anecdote about Latin America or Julia.

The last fight they had was almost a year before my father died. I came home to surprise them one weeknight, and walking down the hall, I could hear my mother yelling. “How would you like me to tell Maricarmen about your twenty-two-year-old? Let me guess, she writes you love poems, and you swoon like a pendejo.”

I quietly retreated from the apartment. That was a week before we found out he was sick. After that it didn’t matter what he had done in his life, though I am sure this is the only thing he needed to regret. He left his girlfriend, and he and my mother spent those last eight months together like they had in the sixties. But when he died, the memories of their love died too. My mother’s anger over his betrayal resurfaced. She had only temporarily swallowed it, and now it was like she had forgotten they were ever in love.

She turns to me and asks why I like Julia so much. “Do you like her just because your father did?”

“Maybe at first, but not now. She’s under my skin. She’s my idol.”

“Idols always break, Maricarmen. Have you ever heard how she was a prostitute? A woman who would be with men for what they could give her. She was very poor when she came to this country.”

“Yeah, I’ve heard. But like anything with Julia, it is a chimera. So many stories, who knows what is really true.”

My mother stares at me. “That doesn’t bother you? What would make you stop loving her?”

“Not everyone has to fall off their pedestals just because they can’t live up to it.”

“What about the people who are disappointed? Those who put you there?”

“They should know that people sometimes have to come down, but the fact that you put them there should mean something, should ensure their permanent place on that pedestal.” I pause. I know what I have to say. “Papi loved you more than anything, more than Julia, poetry, and so much more than . . . anybody else in the world.”

“I think I’m the only one who can measure his love.”

Emboldened, I continue, “No, I don’t think so. You can’t see anymore. Do you think you can ever get back to that place, to the way things were?”

“Maricarmen, some things can never be undone. Especially with memory. Once you know something like that, you always know it. You can never go back to that untainted place, even if you wanted to.”

“So you don’t think you could ever love him again the same way?”

“No, not ever.”

“I still love him. He’s my father. That never changed anything for me.”

“That’s because he wasn’t your husband. You hadn’t given him thirty years of your life.”

“A different love, but love the same.”

“A blind love. Not the same kind of love at all.”

“Is that why you hate Julia so much?”

My mother uncomfortably talks to the picture. “It seems silly, but yes. I think she was your father’s perfect woman. Your father was never much for fanfare. He was quiet, like you. He could get lost in her poetry, and in his reveries, it seemed that he reached a sort of nirvana. Like he had met his ideal woman and they had reached their perfect place. It’s hard to know that you are not necessarily what your husband wanted but instead what he had to settle for in real life.”

“Mother, Father loved you. I can’t imagine he settled for anyone. When he knew he only had so many days left to live, he spent them with you. He could have left and ran around the world, but he didn’t.”

“Maybe he just didn’t want to lose you, his girl.”

“He knew I would love him regardless, and I didn’t live at home, so if he wanted to be a bachelor, he could have just gotten an apartment in New York and seen me anytime.”

“I wish he hadn’t left me with that stain. In the end, I’m left to deal with all the consequences. And some days I hate him so much, even though I don’t want to because he’s dead, and he did everything he could to redeem himself.”

“Maybe not now, maybe in a few more years, but there is always a way back.”

I look back at the picture of my father so close to Julia. With my mother standing next to me, Julia now looks different in the picture. Distracted. Smiling, but not a smile for that place, that moment. And I wonder if that is how my mother sees her. My mother remains silent, and I think back to how she was not very good at storytelling—she would tell me fairy tales, but would always lapse into some feminist manifesto, completely changing the story. The first time one of my teachers asked the class if we knew the story of Cinderella, I raised my hand and repeated what my mother had told me. My teacher looked at me puzzled and burst out laughing. She was what my mother would have called a slave to the patriarchy. Nonetheless, I never again offered my mother’s version of a story.

The event will be over in an hour, so I ready myself to say a few words to the attendees. But I can’t concentrate while reading the words I had intended to say. I knew

my father cheated on my mother, even before she did. I saw him outside his office building with this woman who was not my mother peeling off of him. My heart should have fallen out then, but because I loved my father so much, not even this was wrong. It was like looking at my parents in their youth—two bodies clanging. Love, to me, had always been something more than just two bodies in love. The history of it. The mythic history. That’s what mattered to me.

I get up and take another look at the picture of Julia’s coffin. Staring at all the people, what I notice now is the distance. The gap between these mourners and Julia.

If Julia had been an ordinary woman, a woman who was not a poet but had just remained in her rural Carolina, she would have been deemed “loose,” would have been vilified in her society. Men would have turned the other way and women would not have recognized her as one of their own. But because she was a poet, a talented woman, she could never, ever again be ordinary or held to traditional ideas once she had written a few verses. But what about the common people? Is there no cleansing for them? No redemption? The love of these mourners is pure, magnanimous, and forgiving only because they love her at a distance.

But this is not the way we really love, not the way my mother could ever love my father. Love between two people is up close, disheveled—a mélange of past, present, future love and acrimony. And this is how I must love my mother. Love her the way I want her to love my father again.

“In closing, I want to express my great respect for academics. Everyone gives praise to people who work in the nonprofit sector or were lawyers, like my father, who fought for someone’s rights, or to poets—they get many accolades. We have dedicated this evening to a poet, but I want to tell you tonight that without academics, the writer cannot exist. It is a symbiotic relationship. Generation to generation, who will remember Julia? My father was the one who taught me about Julia, but what if he had not been around? He is just one man. Who will know her if you do not go into your classrooms each semester and teach the poetry of Julia de Burgos?

Love War Stories

Love War Stories